Dynevor Grammar School: A Lesson in Class and Clout

An education in 1960s Swansea, where survival was the first lesson on the curriculum.

For an eleven-year-old boy from a Blaenymaes council estate in 1965, the gates of Dynevor Grammar School didn't feel like an opportunity; they felt like a barrier. The mid-1960s were a time of change in Britain, but my biggest change was the move to this imposing institution. After passing the 11-plus exam, I left my local primary school behind and entered a world with a formidable reputation. The education I received there, however, was less about books and more about the harsh realities of class, authority, and taking a punch.

Clive James, the late Australian writer and broadcaster, once joked that a school report had declared:

"James will never amount to much, but he does know how to take a good punch."

He said he attended a Catholic Christian Brothers school, infamous for its brutal discipline. That line echos in my mind whenever I think about my year at Dynevor Grammar School.

Culture Shock

My first week at Dynevor hit like a cold slap. The school housed boys from age 11 through to 17 or 18 in the Sixth Form, transforming the playground into a miniature prison yard. The sheer size and age gap between students made bullying not just inevitable but systematic. Being shoved around by some hulking sixth-former became an unofficial rite of passage.

The shock ran deeper than mere size disparities. Dynevor was defiantly all-male, no girls to soften the edges, just raw testosterone and casual torment. More than that, it was unapologetically middle-class, wrapped in an unmistakable air of elitism. The Old Dy'vorians' Association, which still exists today, stands as testament to the school's deep roots in Swansea's professional classes.

The Academic Theatre

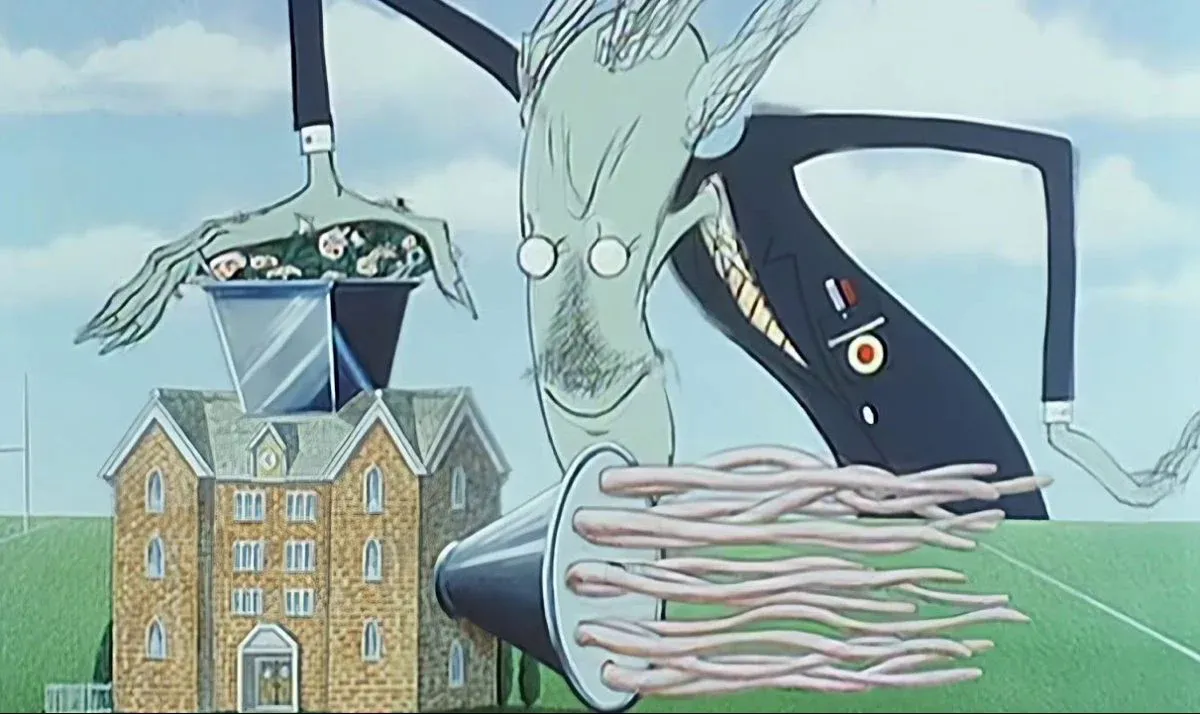

Teachers stalked the corridors in tweed jackets with leather elbow patches, some donning full academic gowns like Oxford dons gone rogue. Many seemed to believe they'd been personally knighted for their mastery of sarcasm. Several appeared to take genuine pride in humiliating their pupils. I wouldn't be surprised if they maintained a verbal abuse leaderboard in the staffroom.

Consider "Ginger," our history teacher, named for his fiery red hair. He wore his academic gown daily like battle armour and taught by mechanically transcribing textbook paragraphs onto the blackboard. We would then copy them into our exercise books, word for word, with no discussion permitted. Occasionally, he'd bark a question at the class. Answer incorrectly, and you'd receive a sharp cuff to the back of the head. His signature move involved grabbing a boy by the sideburns, twisting them painfully, and hoisting the victim onto his toes.

Then came, lets call him Mr. Davies—"Flash" to his students. The nickname had nothing to do with speed and everything to do with the lightning-fast swing of his gym shoe. He would bend you over a desk in full view of the class and deliver "six of the best" for infractions as minor as forgetting your textbook or arriving two minutes late. He didn't teach so much as rule through calculated fear and public humiliation. Compared to Flash, my primary school teachers Mr. Powell and Mr. Williams seemed like pedagogical saints.

Rare Kindness

Not every teacher fit the monster mould. Our elderly French teacher, nearing retirement, harboured a genuine love for France that could be gently exploited. With minimal encouragement, he'd abandon French grammar to regale us with stories of the Paris Métro or the majesty of the Eiffel Tower. He also used a slide projector, revolutionary technology in an era when most teaching involved nothing but chalk and grinding repetition.

The chemistry teacher offered another glimpse of humanity. When illness forced me to miss a test and take it later alone, he marked my paper and awarded me 50%. Seeing the disappointment etched on my face, he quietly changed the grade to 60%. That small act of mercy has stayed with me across the decades.

The Terrible Truth

Here lies the most chilling fact of all: Dynevor Grammar School was widely regarded as one of the finest schools in Wales, staffed by some of the country's most accomplished teachers. If this was excellence, what horrors awaited in lesser institutions?

The school's reputation rested not on kindness or inspiration, but on results achieved through intimidation and the preservation of class distinctions. We were being moulded not just academically, but socially taught our place in a rigid hierarchy that extended far beyond the classroom walls.

Looking back, I realise that Dynevor didn't just educate us; it indoctrinated us into a system where authority was absolute and questioning it brought swift punishment. Perhaps that was the real lesson all along.